And not by drinking Coors Light. That's gross.

For my four-day spring break, I joined a group headed down towards Southwestern Colorado. Originally the trip was sold as a ski-venture, but the discovery that Ska Brewing, a well regarded brewery in this circle, was headquartered in Durango, along with the arrival of spring weather, refocused the intentions of the trip: Colorado, we decided, is the Napa Valley of Beer. And we like beer.

My camera is floating somewhere between here and Mission, so I will have to steal photos from Marion to document the travels.

I headed out soon after parent-teacher conferences ended on Thursday to meet Kim in He Dog and ride with her to Boulder. Our route took me through Wyoming, a state that I had not yet had time to visit. It looked (at least in the corner we ventured through) sort of like Nebraska. Then we pulled into Colorado, which at this point of the night was amazingly flush with traffic and annoying big-box developments. At this point I was not a fan of Colorado.

Our mission on Thursday night was the reach the pub at the

Boulder Beer Company, makers of the well-regarded (especially by Cool Zach) Mojo IPA, and Colorado's first microbrewery. Kim and I left about an hour before the rest of the gang, and we arrived in Boulder around 9 PM. Consulting our directions to the pub, we were surprised to find ourselves pulling into an office park. Upon first consideration, though, I realized that this was a beer company first, and a brewpub second, so the location should not have been a surprise. Nor should have their closing time of 9 PM, either, really. So we had to scratch that one. (At various points throughout the trip I bought bottles of some unusual Boulder beers for later consumption.)

After about 45 minutes of wandering through the CU campus, we finally pulled into a Taco Bell and got directions downtown ("Pull out of the parking lot, take a right and keep going."). There we found

BJ's Restaruant and Brewpub. I was a bit disappointed to intuit that the place was a chain, because there were 3 or 4 other possibilities to choose from, but the food was good. With my pizza I ordered the sampler of the pub's 7 standard beers: a blonde (one of my least favorite styles), a hefeweizen (not usually one of my favorites, but excellent here); a pale ale; an Irish red; a brown (they called this one a "Tatonka Brown," a butchering of the spelling of "Tatanka," the Lakota word for buffalo); a porter; and an excellent Imperial Stout to finish things off. Just after dinner we got a call from the others that they had arrived and were at the

Southern Sun brewpub. After realizing this was about a 15-minute drive away, we were able to get Kate to pick us up. At Southern Sun I tasted the porter that the group had ordered, and then got another sampler to share with the group. I chose some slightly more unusual beers this time: a Wit that was so heavily spiced with chamomile that it tasted like liquid soap, an interesting ginger beer, a honey ale, and a variety of pale ales. Before it got too late, we found our way to a Days Hotel and rested up for the next day of driving.

The next morning we headed out for the mountains, which looked like this:

After about an hour of driving, we stopped for gas in a small town. It was a beautiful day, slightly cold but sunny, and I was surrounded by mountains. Maybe I liked Colorado after all.

At Russ's recommendation, we pulled into Salida for lunch. We came in on a small local highway, and passed a lot of trailers and run-down houses. The place struck me as a hard-on-its-luck mountain town, a beautiful place still struggling to hang on. Then we got to Amica's, our intended restaurant.

Any town with wood-fired pizza and microbrewed beer is probably doing alright. Turns out if you drive in another way, Salida looks like the decently yuppie ski town it really is. What can you do?

Amica's was excellent though. I had a great portabella mushroom sandwich with a dopplebock on the side. Below you will see the beautiful array of colors that our beers offered:

The fellers posed for a photo in Salida.

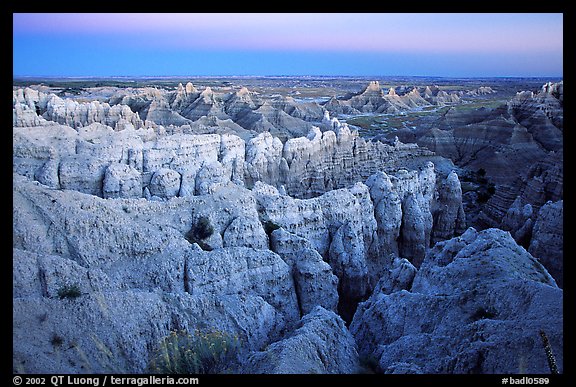

After driving for a few more hours alongside the Sangre de Cristo mountains, we took a break from beer for our first outdoorsy spot: the Great Sand Dunes National Park.

It looks like we're in the desert somewhere. But all this sand is blown right up against the Rocky Mountains. We were at 8,000 feet at this photo, which explains why I was heavily winded after this brief jog. The park includes the tallest dunes in North America, including one with a 750-foot vertical.

Just south of the dunes is one of Colorado's 14,000 footers. Also, Kate is rolling in the sand.

As we were repacking the cars after the dunes, a ranger came over asking if we were headed into the backwoods area. Sadly, of course, we were not. We were headed on to Durango, where Darius' father lives. This leg of the trip took us back up into the mountains and over the Continental Divide. The snow was packed thick:

On Saturday morning we got up early to head out on a supposedly "moderate" hike before beginning our tour of Durango's brewers. Russ and I had picked out the Hogsback trail the night before.

The trail turned out to consist of a very steep climb up a barren mountain. Which I thought was awesome. A few times I sprinted up the very sharp inclines. Seeing how others responded to the altitude, it seems that I am lucky that I stay in relatively good shape.

There were some nice views from the top. Turns out Colorado ain't so bad, after all.

Hike completed, we headed to Durango proper. Flipping through the Durango tourist magazine at our hotel, I found an article that confirmed our suspicious: Durango itself is almost officially the Napa Valley of Beers. A town of 15,000 residents, it produces 15,000 barrels of beer per year, and each of its 4 breweries is entirely green.

Our first stop was

Carver Brewing Company. Since they do not bottle or distribute their beer, it was an ideal stop for lunch: whatever we wanted to try, we had to try in house.

Being a completist, I, of course, had to try them all. So here I am with my next sampler. So many mini-beers!

That didn't leave much room on the table for my lunch. If I can remember everything, the selection included a blonde (meh); a raspberry hefeweizen (tart, not sweet, and perhaps causing me to reconsider my bias against fruity beers); a pale ale; an oatmeal pale ale, a slightly creamier variation on one of my favorite styles (we bought a growler of this one to take back to Darius' dad's house); a well-balanced amber ale; an excellent Irish red; a brown; two variations on the same scotch ale, one on keg and on on cask, the latter being slightly less carbonated and with some sour (in a good way) overtones from the cask; a barleywine (first one I've ever tried!); a porter; and a chocolate stout. Quite as an assemblage. Probably the most consistent selection of all the brewpubs we tried.

After Carver's, we headed to

Ska Brewing, Durango's largest brewery. And by largest, I mean it is a small office tucked away in the corner of a small town. When we pulled into the dirt parking lot, a crew of ski bums were sitting around in camp chairs enjoying the sun and beer. Inside, the tasting room was about as hip as you would expect from that name. Lots of homebrewing supplies, too. We almost bought a kit to make an American Pale Ale, but I decided it was overpriced. I took a post-sampler break and just took small sips of what everyone else ordered. I bought a few samplers out of this cooler for later consumption, though.

At the end of the day, the trunk of the other car looked like this. Our trunk was not too different.

On Sunday, Russ, Katie, Darius and I decided to take advantage of our last free day in the Rockies for another hike. Russ is serious about his hiking and planned a 10-mile hike that could be extended into a 13-miler or so, if we were feeling great. The first snag in the plan occured when the road we intended to drive down was closed, meaning we had to join the trail about a mile and a half earlier than planned. We struck out from the head of the Colorado Trail, which winds 480 miles all the way back up to Denver. The hike was spectacular: there were still two or three feet of snow packed on the ground, so we were walking over that. By the earlier afternoon, as things started to warm up, the snow started to soften, and my foot would punch down about a foot with each step, which reminded me that I need to get some more waterproof shoes for hiking. We had intended to reach a waterfall when we got to the top of the climb, but we had misread the map, and that would've required tacking another 7 or so miles onto what was already a 9-mile trek. But we ended up pleasurably exhausted.

Those who chose not to join us on the hike spent the day at another of Durango's brewpubs, Steamworks. And by spent the day, I mean they were there for literally 5 hours. By the time we arrived they were very good friends with the waitstaff, and as more workers got off their shifts, they would join us on the deck to hang out. Apparently they have a tradition of doing stout slammers, which consists of chugging 10 oz. or so of their stout. So we did it. Here is the aftermath:

After leaving Steamworks, we had an excellent dinner at a Himalayan Restaurant before heading to bed early so we could make the 15-hour drive the next day without any real problems.

Sadly the trip home did not involve any brewpubs. We considered stopping in Alamosa at the

San Luis Brewery, but it did not fit into our plans. I did buy a bomber of their Mexican Lager at a liquor store, however.

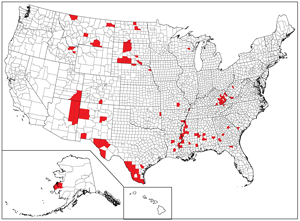

Alamosa has been hit by an alarming number of cases of Salmonella over the past few days; it seemed that the municipal water supply was tainted. When we stopped at a gas station to use the bathroom, we found the water shut off and we had to use hand sanitizer instead. The beers stores were taking full advantage of the crisis, though. We passed one, on the way out of town, that gave the perfect solution: "Can't drink the water? Have a beer."

Fair enough.

We went up--straight up--to the top of this ridge.

We went up--straight up--to the top of this ridge. Climbing.

Climbing. Making the final push.

Making the final push. View of the next mountain.

View of the next mountain. On top.

On top. Descending again.

Descending again.

It looks like we're in the desert somewhere. But all this sand is blown right up against the Rocky Mountains. We were at 8,000 feet at this photo, which explains why I was heavily winded after this brief jog. The park includes the tallest dunes in North America, including one with a 750-foot vertical.

It looks like we're in the desert somewhere. But all this sand is blown right up against the Rocky Mountains. We were at 8,000 feet at this photo, which explains why I was heavily winded after this brief jog. The park includes the tallest dunes in North America, including one with a 750-foot vertical.

Just south of the dunes is one of Colorado's 14,000 footers. Also, Kate is rolling in the sand.

Just south of the dunes is one of Colorado's 14,000 footers. Also, Kate is rolling in the sand.

That didn't leave much room on the table for my lunch. If I can remember everything, the selection included a blonde (meh); a raspberry hefeweizen (tart, not sweet, and perhaps causing me to reconsider my bias against fruity beers); a pale ale; an oatmeal pale ale, a slightly creamier variation on one of my favorite styles (we bought a growler of this one to take back to Darius' dad's house); a well-balanced amber ale; an excellent Irish red; a brown; two variations on the same scotch ale, one on keg and on on cask, the latter being slightly less carbonated and with some sour (in a good way) overtones from the cask; a barleywine (first one I've ever tried!); a porter; and a chocolate stout. Quite as an assemblage. Probably the most consistent selection of all the brewpubs we tried.

That didn't leave much room on the table for my lunch. If I can remember everything, the selection included a blonde (meh); a raspberry hefeweizen (tart, not sweet, and perhaps causing me to reconsider my bias against fruity beers); a pale ale; an oatmeal pale ale, a slightly creamier variation on one of my favorite styles (we bought a growler of this one to take back to Darius' dad's house); a well-balanced amber ale; an excellent Irish red; a brown; two variations on the same scotch ale, one on keg and on on cask, the latter being slightly less carbonated and with some sour (in a good way) overtones from the cask; a barleywine (first one I've ever tried!); a porter; and a chocolate stout. Quite as an assemblage. Probably the most consistent selection of all the brewpubs we tried.